Hello Restless Wonders,

Thanks for all the love about last week’s announcement of our nomad plans. Jeepers there was a lot of love! How can I feel like I’m doing this alone when you’re all here with me?

Thanks as well to the hefty bunch of you who decided to become a Restless Rebel and support these weekly words with the cost of a coffee a month. That warms my soul and has spurred me on through this week’s post.

After a wee poll, I was rather excited to discover that 97% of you said you’d like to know more about how the process of creating a book.

So this is a behind the scenes peek-a-boo about how I go from having an idea for a book, to bringing in into the world.

I very much enjoyed jotting this all down and, in the process I realised that I may need to write a book, about the craft of writing a book.

Go figure 🤷🏼♀️

Much love and catch you next week,

Anna xx

How a Book Gets Made

I believe all of us have a story to tell.

Whether you want to write it down and share it with the wider world is another thing, but there’s a space on a bookshelf somewhere, waiting for your story.

I’ve published six books in the past eight years. One of my books is traditionally published, but I’ve released most of them independently. As in, I am the publisher. Ooo err.

It costs me around £5,000 to pay a team of freelancers to help me produce each book. But I choose to do this, and be an indie because…

I like the idea of not having to wait ‘for permission’ to share a story with the world.

I get to keep all the rights (and my kids then can then own the rights after I peg it).

It’s very freeing. I can do what I like with the books — make special editions, change them, make BoxSets, give them away.

I make far more per book sale than a traditional publisher would pay me. (You usually get 10% with a traditional book deal, and 35-70% by being indie).

So far, the books make at least 10 x what it costs me to produce them. So the maths of being an indie author makes sense, and ultimately — I GEEK OUT on this process I’m about to share with you. It’s what gets me up in the morning many days!

Being traditionally published is right for lots of people, but this is the way to go for me.

The Chapter Half-plan

I approach writing a book the way I approach life and adventures. No structure is pure chaos. Too much structure is suffocating. Somewhere between the two is where the party is at. So I always start with a loose plan.

I sit down with an actual pen and actual paper and I think back through the journey. Because I write about things that have happened in real life (fancy term = memoir) it’ll all have taken place over a certain time period. This means I can break the overall story into natural sections.

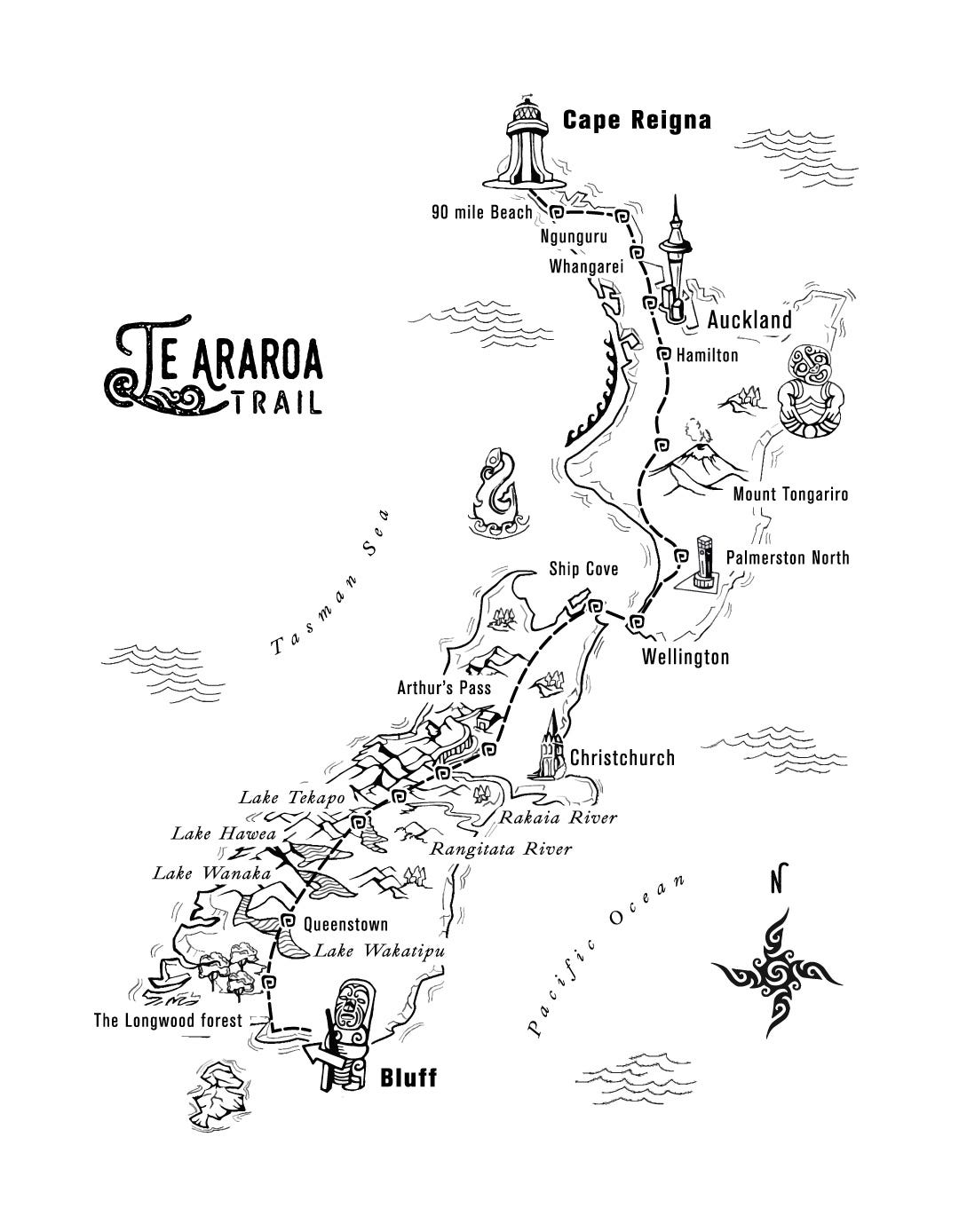

So for The Pants of Perspective, which was about a 6-month journey along the Te Araroa Trail, I’d write something like:

Chapter 1: The build up — the decision to go, pre-adventure nerves, logistics

Chapter 2: Getting Ready in NZ

Chapter 3: The start! Bluff to Longwood Forest

Chapter 4: Longwood to Queenstown

And so on…

I’ll just let my mind go for it and by the end I’ll have something that’s between 25 - 30 chapters.

I know that this won’t end up being the final structure of the book — the start and end point of these chapters will change as I go along, but the main thing is that I’m on my wa-hey.

I have started the process of creating.

That is monumental.

With some kind of structure to work from, suddenly the book stops being a mystical thing floating around in the atmosphere. It becomes concrete. No longer daunting and, so long as I don’t think about all 30 chapters and only focus on one chapter at a time, it seems do-able.

Now, instead of being terrified about starting, when I come to write, I’m like a kid opening up a colouring book — all I need to do is add colour to those chapters. I don’t even need to colour within the lines. Imagine.

The added bonus of the process of making this loose structure is that it primes my brain beautifully for the next stage, which is… The shitty first draft.

The Shitty First Draft

There’s a misconception when you’re writing memoir you should begin by writing about what happened at the beginning and finish by writing ‘the end’.

My brain doesn’t work like that. Memories don’t work like that. The flow of our daily life isn’t linear, so why would the writing process be any different?

When it’s time to write the first draft (and after reminding myself that this draft really will truly be terrible) I let go of where I think I should begin and instead I open up my laptop, I shut my eyes, I let out a deep breath and I think, ‘Where do I want to go today?’

I let my brain float through the memories. I think about conversations I’ve had, characters I’ve met, about the sights and smells and sounds of places — things that stick out in my mind. I just let my brain go for it and wait while it hovers briefly over the special moments in the journey.

When I get to a moment where I linger, I think ‘Ah ha! This is it. This is where we’re going today!’ I open my eyes and let whatever I’m thinking flow onto the page.

I write for as long as I want to on that memory, then move onto another or just end the writing session when my juju runs out.

These writing sessions are a happy place for me. Because not only have you had the fun of the adventure, but you get to re-live it all over again and solidify those memories. Double the fun.

Remember and Repeat

Every time I come back to the book manuscript from this point on, I repeat this process. I think about where I want to go, and what are the coolest stories — the ones that I would tell my friends down the pub — and I go there.

After many months, when I have exhausted all the cool stories that come to mind, it’s time to go back and fill in the gaps.

This is a harder task. It’s a clunky process and there’s usually a lot of research and fact-checking involved as I go.

The Voices

I can’t tell you about the process of writing a book without giving an honourable mention to ‘The Voices.’

During this shitty first draft, your head is not only filled with stories needing to go onto the page, but also with unwelcome voices commenting on your writing.

The Voices will say things like:

This is terrible, no one is going to read this

A five-year-old could write better than this.

This is ninety per cent waffle.

What’s the point in writing this anyway? No one is going to buy this book.

There is nothing unique about this story.

No one is going to believe that this happened.

Stop being so dramatic.

Think of everything that your inner critic says to you on the daily and turn it up to loud.

At this point, I like to remind myself of an amazing book by Anne Lamott called Bird by Bird — dedicated to the process of writing these shitty first drafts.

Anne talks about how to view these critical voices:

“Close your eyes and get quiet for a minute until the chatter starts up. Then isolate one of the voices and imagine the person speaking as a mouse. Pick it up by the tail and drop it into a mason jar. Then isolate another voice, pick it up by the tail, drop it in the jar. And so on.”

Having written six books, I can confirm that these voices never go away. The mice are always there, at the page waiting for you. Trying to distract you from what you are doing and hoping to convince you that your words are not worth putting into the world.

They are, of course, wrong.

Self-editing

After navigating through The Voices, and having got the first draft to something that feels marginally less shitty by your own standards, then comes my all-time favourite part of the book creation process.

I print the whole draft out, double spaced on actual paper and I go at it with a beautifully coloured pen. I do this with a cup of tea, curled up in a big chair, imagining that this might be how a person could end up reading my words.

I mark up many, many changes in the margins and then put them back onto the online version of the manuscript.

When the manuscript is at place where I’m happy(ish) with it, I know that it needs some outside eyes. So it’s time to pass it on to a structural editor.

Enter… The Professional Editors

My primary editor — Debbie — is like a more sensible and grounded version of me. She has the same sense of humour, loves travel and the outdoors but hasn’t done crazy big adventures and so is understanding of where most people are coming from when they read the books.

Debbie queries things, asks me to clarify sections, to expand parts and we sometimes shuffle the stories around too.

We have a right old laugh, working alongside one another in stages — me sending her a few chapters to edit, her sending them back — little chunks of the book, accompanied by comments, flying back and forth between us.

After the structural edit, the book will go to a separate line editor or copyeditor. This person is not only checking your grammar (which can be interesting because I often make up my own rules for grammar) but they’re also doing the final trimming of the words.

So they’ll suggest removing surplus sentences or maybe the odd paragraph here or there — anything that doesn’t add to the flow story.

This process (and even the earlier, more structural editing) isn’t always easy. When the editor is suggesting cutting a part that I really love, it can be hard not to take it personally.

Especially when you’re writing from the heart about vulnerable things. At the start of my author journey, if the editor wanted to cut some words — it tapped into a belief that my words weren’t worthy of sharing. That they weren’t funny enough or interesting enough. It knocked my confidence or made me defensive.

I’ve learned over many books to be objective about the comments, and now the editing process is much easier. If it happens that I’m struggling with some feedback, I’ll walk away from the laptop, have a cup of tea and come back to the editor’s comment with fresh eyes.

Ultimately, the editor is there to help and they make SUCH a difference in creating a better book — but that doesn’t mean there’s not a good healthy debate from time to time.

As a general rule, I end up accepting 80% of the editor’s suggestions and push back on 20% of them.

After the copyedit, the manuscript goes to a proofreader for the final dotting of t’s and crossing of i’s. In the past, my Great Aunt Ann has been my proofreader. She is a US-based academic with a laser-sharp eye for detail.

Formatting & Illustrations

Once the words are in a good place and the manuscript has been proofread, it goes to the designer to be ‘formatted’.

That means turning it from a word document into something that’s beautifully spaced, in a nice font, laid out in the size it needs to be for the paperback version of the book.

There is software to do this yourself, but I like to work with designers because a) It’s fun and b) My brain isn’t great with fiddly detail.

I’ve always worked with Off Grid as my designers because they do illustrations too, so I often commission map illustrations to go along with the books.

From a business / money making perspective, it doesn’t make much sense to spend more money on including these maps - but I’m driven by my heart. These illustrations break the book up and add even more personality, plus they help those of us with wayward attention spans to work out where in the world we are, at that moment in time.

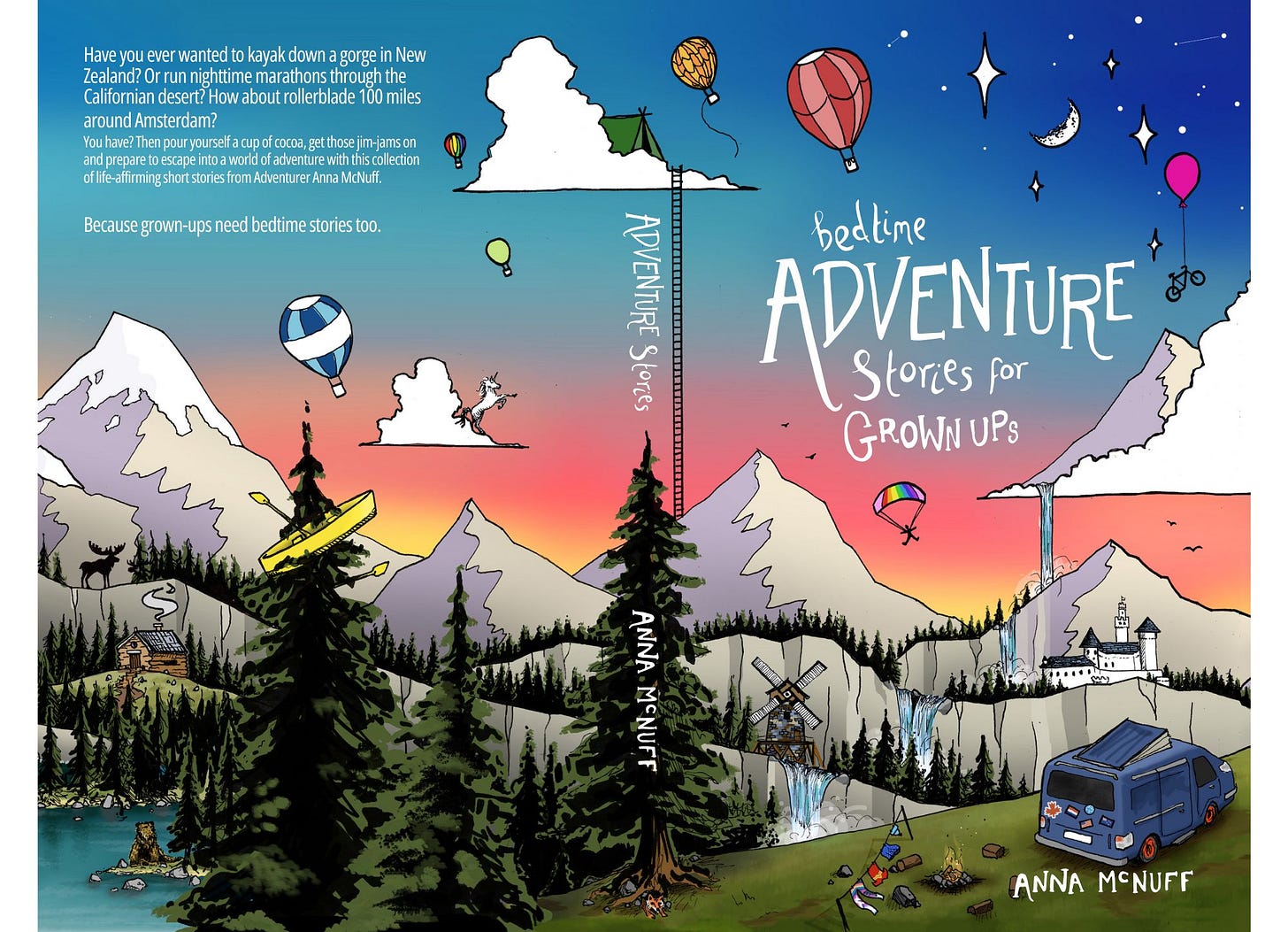

The Book Cover

Somewhere along the line, usually when the book goes to the editor and I have a rough idea of how many words it’s going to come out at, then I’ll get in touch with the designers to make a start on the cover.

Just like the writing part, I get very excited about this process too. The feel of a book is such a lovely thing to work on. To turn your story into a physical object and be able to hold it in your hand is satisfying. It makes me squeal with delight every time I get to see the first printed version of it and it never gets old.

If you’re playing by the ‘rules’, then a brief for a cover design should start with what other books in the same genre look like, so that the cover fits in with those. i.e. ‘here are a load of other books about a running adventure’

Crime thrillers feature silhouettes and large title text, romance books feature topless men and horses, fantasy books are often dark and swirly etc.

I follow the genre rules to some extent. That’s where I start, but my heart leads my head and I end up going with whatever cover lights me up inside, as opposed to the one that I think will sell the most.

I may not die rich, but I’ll die being super proud of the books I’ve put out into the world.

It’s a long process of back and forth and I went through 27 iterations of the cover for Barefoot Britain.

And every book is unique…

For Bedtime Adventure Stories for Grown Ups — this wasn’t a category for bedtime story books for adults (shocker), so I briefed a local illustrator, based on what kids bedtime story books look like.

He nailed it.

Final Checks & Audiobook!

The fun isn’t over just yet… Now it’s audiobook time!

This has been one of the greatest joys of being an author, discovering the love I have for sharing stories out loud. It took a while to get to grips with doing it, but now I’ve got a slick process to create an audiobook.

I go and see my main-man, Soundshack Greg, who built a recording studio at the end of his garden in Cheltenham. I sit in a booth with some honey and lemon on standby for my tired throat, and record in 3-4 hour stints. After that time my brain turns to smush and I make too many mistakes.

Greg and me laugh A LOT — especially when I’m messing around with accents. I was once trying to do the accent of an older Canadian man when Greg paused the recording and said, deadpan: ‘Anna, just checking on this part — did you want this guy to sound like he might murder you in your sleep?’

This wasn’t my intention.

Each book, which is c10 hours of listening time, takes me c23 hours of studio time.

It’s hard work but, as an audiobook fan myself, it’s such a lovely thing to listen to the author read the book. It’s like you’re hanging out with them one-on-one.

AI is getting so good that there’ll be plenty of AI-narrated books out there soon, but I’ll always narrate my own. Because as robots take over the world, all we can do is double down on being human.

Upload and Go!

After then, I whip up an eBook version of the book using some funky software (Vellum) and with all the versions of the book done — upload it to various platforms — KDP (Amazon) for print and ebooks, Findaway Voices and INaudio for the audiobook, Ingram Spark for bookshop distribution, Book Vault for my own bookshop, and kapoof! It is out into the world.

And Relax?

Not a chance. Because I am the publisher and the PR and the marketing all rolled into one, I then need to tell everyone I wrote a book.

I usually have a big virtual launch partaa-y, do some shouting on social media, give some podcast interviews — do what I can before I burn out.

Then I get excited about an idea all over again, and start working on the next book…

This is one of the best posts I've ever read on the creative process not just on substack but anywhere!

Love it, love it, love it!

Hi Anna,

I love all your books and listening to your adventures. Do you write notes or keep a diary while you are on your adventures so when you start writing you can refer back to it. There is always so much detail in your books and I’m wondering how you remember it all? 😊